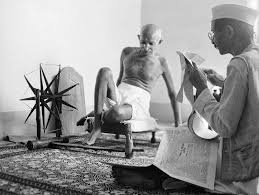

In the pages of history, there are not many photographs as reminiscent and strong as the one of Mahatma Gandhi sitting in front of a spinning wheel. This photograph, taken by acclaimed American photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White in 1946, is an iconic portrayal of a nation’s struggle for freedom and an individual’s commitment to simplicity, self-sufficiency, and peace.

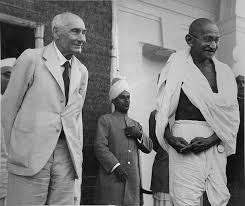

Margaret Bourke-White, famous for her significant conflict time pictures, showed up in India during a time of gigantic political disturbance. The nation was on the cusp of independence, overflowing with confident yet uneasy energy. Bourke-White’s essential mission was to record the quakes of this independence movement undulating through the Indian subcontinent. During her time in India, she had the valuable chance to meet Mahatma Gandhi, a pivotal figure driving the battle for independence.

Margaret Bourke-White: Her Pictures Were Her Life by Susan Goldman Rubin gives a personal knowledge into her journey

At the point when Bourke-White met Gandhi, she was interested by his way of thinking of peacefulness and self-sufficiency, addressed by his demonstration of spinning his own fabric. The simplicity of this act stood out pointedly from the intricacy of the political atmosphere, making a convincing story that she wanted to catch.

This interesting situation introduced extraordinary difficulties and potential open doors according to a photography viewpoint. Bourke-White’s camera of decision was the Rolleiflex, known for its uncommon form quality and accuracy optics. She favored highly contrasting film for its capacity to emphasize differences and surfaces. This proved to be useful while capturing the juxtaposition of Gandhi’s straightforward clothing and the unpredictable plan of the spinning wheel.

The Art of Photography

For anyone keen on investigating the specialized parts of such iconic photographs, The Art of Photography, An Approach to Personal Expression by Bruce Barnbaum makes for a convincing read.

In the photograph, the strength and determination emanating from Gandhi’s concentrated look are balanced by the tranquility of the scene, offering watchers a brief look into his unstoppable soul and the peaceful defiance that portrayed the Indian independence movement.

The image wasn’t simply a masterpiece; it became a symbol. The spinning wheel, or ‘charkha,’ was not only an article in the picture. It held its own significance. For Gandhi, it was a device of dissent against English made merchandise that overwhelmed Indian business sectors. By spinning their own fabric, he contended, Indians could become self-adequate and autonomous. This feeling resounded with a large number of Indians and became a critical part of the freedom movement.

Bourke-White’s photograph of Gandhi with his spinning wheel assumed a significant part in molding general assessment and energizing help for the Indian independence movement. It exemplified the quintessence of a groundbreaking period in history in a solitary, strong casing.

India acquired independence on August 15, 1947, barely a year after the photograph was taken. The picture, nonetheless, keeps on holding its place ever, connoting a second when a nation turned its own predetermination.

Bourke-White’s commitment to her art and her intense attention to the socio-political environment empowered her to make a picture that transcended geological limits and keeps on motivating ages. It just so happens, an image to be sure can merit a thousand words, and at times, much more.